An exhibition of installation Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore

Participating Artists : Sheila Gowda, Rasna Bushan, Raghavendra Rao, Om Prakash, Ravishankar Rao, P.C. Stephan, Surekha, Sudharsan, Somasekara, Dhanaraj Keezhara, and C.F. John

The installation was in the form of a spiral maze. Two intertwined spirals over 100 feet each in length and 6 feet in height with 4 feet space between each layer were installed. (please refer to drawing). The material used was plastic. The transparent surface of the plastic made it possible to weave together visuals and the viewers from different layers. Hence, contemporaneously the images, installed space, and viewers become integral components of the work.

Visuals and texts, both in English and in Kannada, were taken from various counter cultural/religious movements from history that countered the dogmatic religious stands of the time. These visuals were painted or drawn on the plastic surface of the spiral. Two parallel mirrors were placed facing each other in the center of the maze where the viewer could see him/herself. The spirals placed emphasis on self-realization rooted in fundamental human values in relation with the Earth…

C.F.John

Details of the work

Size: 40ft x 40ft x 6ft.

Medium: plastic, printing ink, mirrors and bamboo poles

Context

The nineties began with a vast churning, drastically changing the way we saw the world, our lives and relationships. A new world was unfolding, sensing a deep restlessness and a floating anxiety in the air that permeated the gut.

“The war will be televised”

The live telecast of the gulf war in august 1990, the live images of bombing from the front lines of the battle: and the vicarious appropriation of a new kind of heroism to be experienced like a 'Video Game War'. Terror was presented as a virtuous act with the pretext of saving the world and to bring a 'new world order' to uphold 'decency and humanity'.

Even as this was happening, my interest continued to focus on trying to comprehend the earth-centered visions of indigenous communities. I spent time with different communities including the adivasi to gain insight into their life and vision. I spent time with them, walked with them, and listened. They shared from their life, their memories, their myths, their history, and their festivals.

To top the anxieties resulting from the gulf war, a new economic policy was introduced in 1991 by the P. V. Narasimha Rao – Manmohan Singh government. We foresaw the serious impact on the lives of agricultural, tribal and traditional fishing communities, with whom we were all closely connected. Life in all aspects were changing - social, cultural, economic, political and spiritual. Looking back, I see the Gulf war was a precursor to serial terror attacks either by the state or by sectarian communities. On the 6 December, 1992 Babri Masjid was vandalized and demolished. Myths, fictions, history, rumors, hatred, revenge fantasies, faiths and politics were all mashed up into a ball pushed down our senses into our gut.

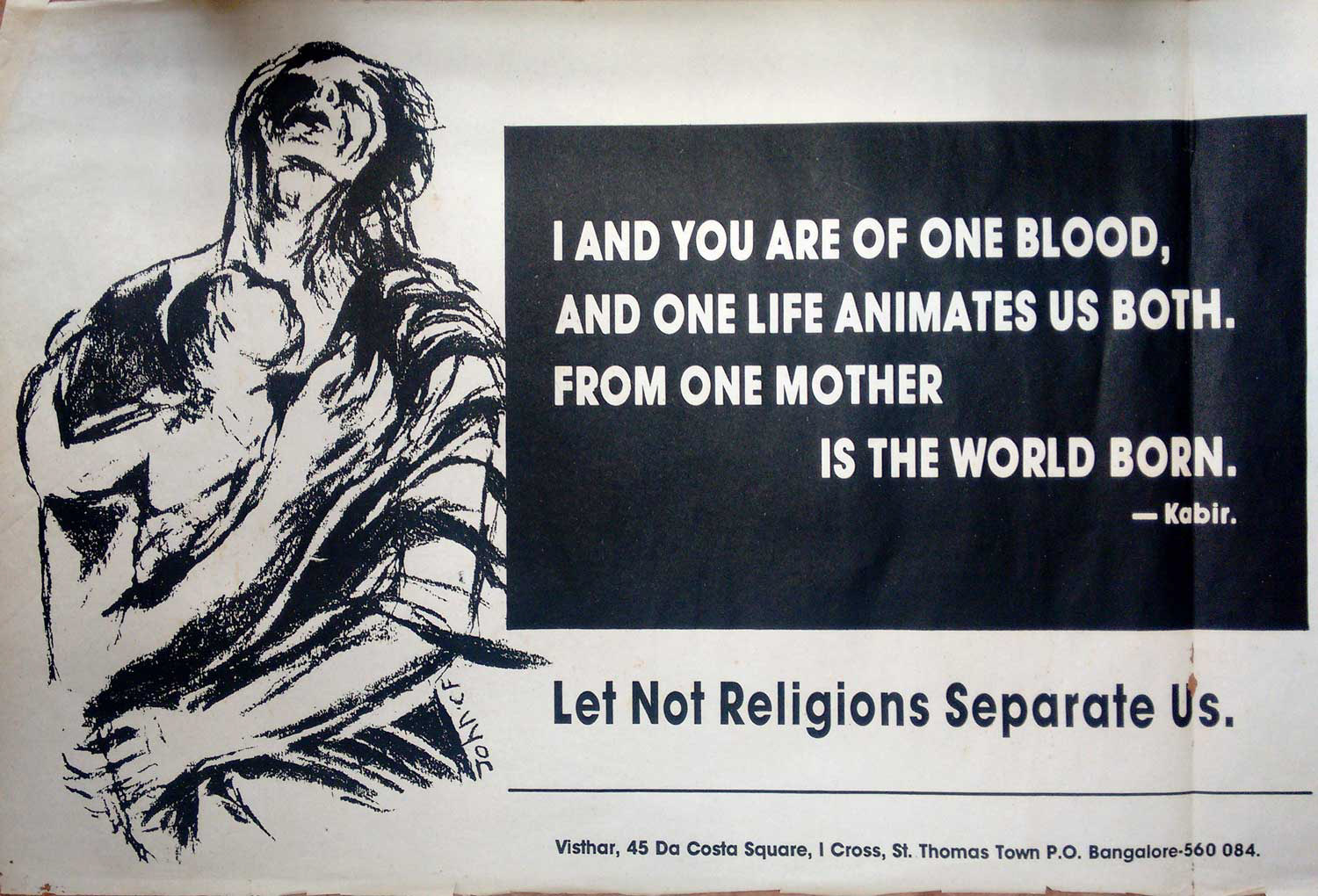

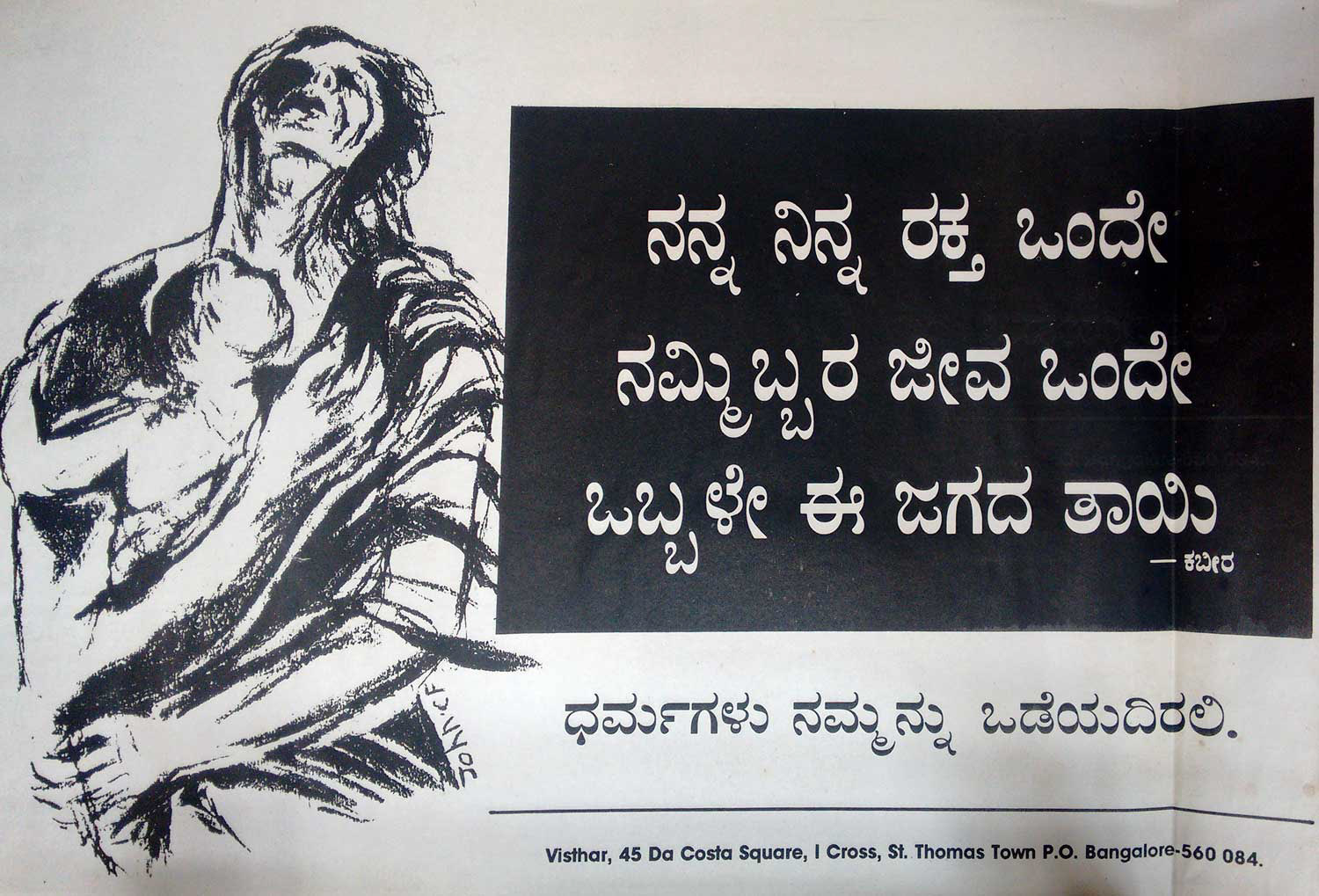

On the morning of 7 December 1992 morning, we at Visthar sat together to discuss what may be done from our side to affirm and uphold the nation's collective consciousness that celebrated a pluralistic vision. I did a drawing - it was a strange drawing- a cliché if your will -- a mother carrying a baby and running away from terror. Mercy selected a poem from Kabir to go along with it to compose a poster. We printed it in four languages -- Kannada, Urdu, Tamil and Englis -- and pasted them on the street walls in Bangalore and also sent many to various NGOs in different parts of Karnataka. In one district, it seems, the collector gave an order to display this poster in all government offices and got the police to paste it at many public places. They asked for a few thousands more copies for their use. Later the Bangalore Police too, with guidance of A.R. Infant (IPS), used the same poster in the city during their campaign for communal harmony.

I took these images to different newspapers to get them published. It was a time of immense tension. Moving around to the press and other places was very risky as on many streets riots were breaking out causing injuries and even fatalities. Many of the reported deaths were due to police firing. There was no internet to send images to the press. This was the first time I became deeply conscious of my own body: I felt that I had no option but to carry myself in this body, like water in an earthen pot. When the pot breaks, the water flows out. I had to move in this body and my life in this form would end when this body is destroyed. More than two months of intense work on this issue made me no more able to stand this vicious sense of violence in the name of religion. I took to carrying a poem by Kabir in my pocket

‘You and I are of one blood, and one life animates us both,

From one mother is the world born’

From one mother is the world born’

let not religions separate us.

Kabir became more close to me. I also heard this poem by Basavanna chiming in my conscience.

The rich

will make temples for Siva.

What shall I,

a poor man,

do?

My legs are pillars,

the body the shrine,

the head a cupola

of gold.

will make temples for Siva.

What shall I,

a poor man,

do?

My legs are pillars,

the body the shrine,

the head a cupola

of gold.

Listen, O lord of the meeting rivers,

things standing shall fall,

but the moving ever shall stay.

things standing shall fall,

but the moving ever shall stay.

Translated to English from the original Kannada by A. K. Ramanuja

I wanted to exile myself from this city and spend some days at a place where the communal issues were not a concern. So I went to Wayanad and spent some days there with an Adivasi community. For the tribal, the issue of Babri Masjid and questions of religious fundamentals were not a matter of interest or concern. It was therefore an escape for me from that time of our nation, maybe an escape from the Nation itself. In fact our nation holds different times and histories, simultaneously. In Wayanad, I was fortunate to have the help of K.J Baby and Shirly in getting some Adivasi men and women to spend time with me.

Each day, early in the morning, we would start walking deep into the forest. We carried a bag containing beaten rice, pieces of cut coconut, jaggery, banana and water for sustenance. It was not just a walk in the woods, but a journey to a different time and consciousness, a consciousness that hitherto lay dormant. I saw my body dissolving and the life beyond death. Tall trees stood in stoic watch as I intruded into their domain.

Silent witnesses.

I wondered what the trees thought of me, as I walked among them. I felt stripped and a sense of shame, at the same time sensing acceptance. The trees continued their watch from the heights making me uneasy. Kalan, one among us, said it was time for us to sit, rest and eat. On leaves, he made eight portions of what we had brought to eat. I wondered why eight when we were only seven? He then took one portion to the base of a tall tree. There were two of them next to each other -- Anna and Thambi. They stood as gargantuan guardians of the forest. It is believed that there was a different forest at that place a long long time ago. Then people came to cut down the forest and cut most of the trees. But when they came to these two, something stopped them. They stood on. Now this is a different forest, but these two trees continue from the older forest. He spoke to the trees as speaking to one familiar. He did not use false honorifics:

"…This person who has come with us is John. He asked us if we could take him to these places

and tell our stories to him. So we have brought him. Our purpose is only to walk these places, nothing else. Please accept us. Now we are hungry and want to eat something. Please join us and take a share from what we have brought".

and tell our stories to him. So we have brought him. Our purpose is only to walk these places, nothing else. Please accept us. Now we are hungry and want to eat something. Please join us and take a share from what we have brought".

It was plain talk, no tone of any ritual. After this we ate.

Most times our walks were silent. I only heard the sounds of of our own bare feet on the earth, the crush of dry leaves, and the sound of our own breath, as well as the cry of birds, the whisper of breeze, and the creak of the trees. It was a silence that merged our bodies with the body of the forest – the trees, rocks, air, soil and water. At other times they would gift me stories, histories, myths and beliefs, as well as the memories of their tragic times. It was in the same soil, less than three decades ago they used to hear the sound of boots. It was the hunt for naxalites. At times in the thick darkness of night, the sound of boots would move towards a hut. The kerosene lamp would go out with a shrieking cry. A thick silence of terror that the forest never knew before weighed down the nights.

During those visits, I used to give paper and pastels to some of my new companions to draw. I asked them to draw freely what came to their mind also their perception of the trees, land and water. Their pictures were homes for trees filled with honey combs, streams, rocks, wild boar, elephants and other animals. Some of the trees were more than mere trees. A woman, Bommy, drew a tree, its roots coiled into a womb that birthed light.

They had a festival for the Tree God. A simple ritual under the tree. I sensed the absurdity of our mainstream faiths. We hate, fight, and kill in its name – in the end, nothing but stone and cement. We demolish and build. Money and power are the new gods. For the Adivasi, the tree is a living god, subject to not worship, but affectation by the environment around. This god stood unprotected in the rain, mist, sun and wind. A mosque or temple may be built in a year if one threw enough money at it. But a tree, the vulnerable sapling grows only with nature’s love and must many decades to stand for centuries. If that tree dies, another tree takes its place. So it is with the mind of the adivasi. It does not fixate on dogma and on one single form or one specific place. It is more fluid and organic. It is so also the nature of true spirituality. Any true seeker knows how truth presents itself, both revealing and concealing at the same time to remain a mystery. Money, power and dogma have no place here.

The order and dharma of this worldly kingdom, and the order and the dharma of Divine will continue as riddle. The Divine order reveals itself as both simple and at the same time veiled. I have heard of a ritual from a tribal community. I do not remember if I heard this from Wayanad or during a visit to a tribal community in Bihar. When the tribal leader is unable to resolve an issue, he climbs a tree to spend some time there. It is believed the spirits meet him there guiding him towards a resolution. The tree is a ladder between this world and the world of spirits. He goes beyond the dharma of the community -- the veiled vision defined by the pressures of time -- by climbing the tree to redefine their own dharma to reconnect it to the greater dharma.

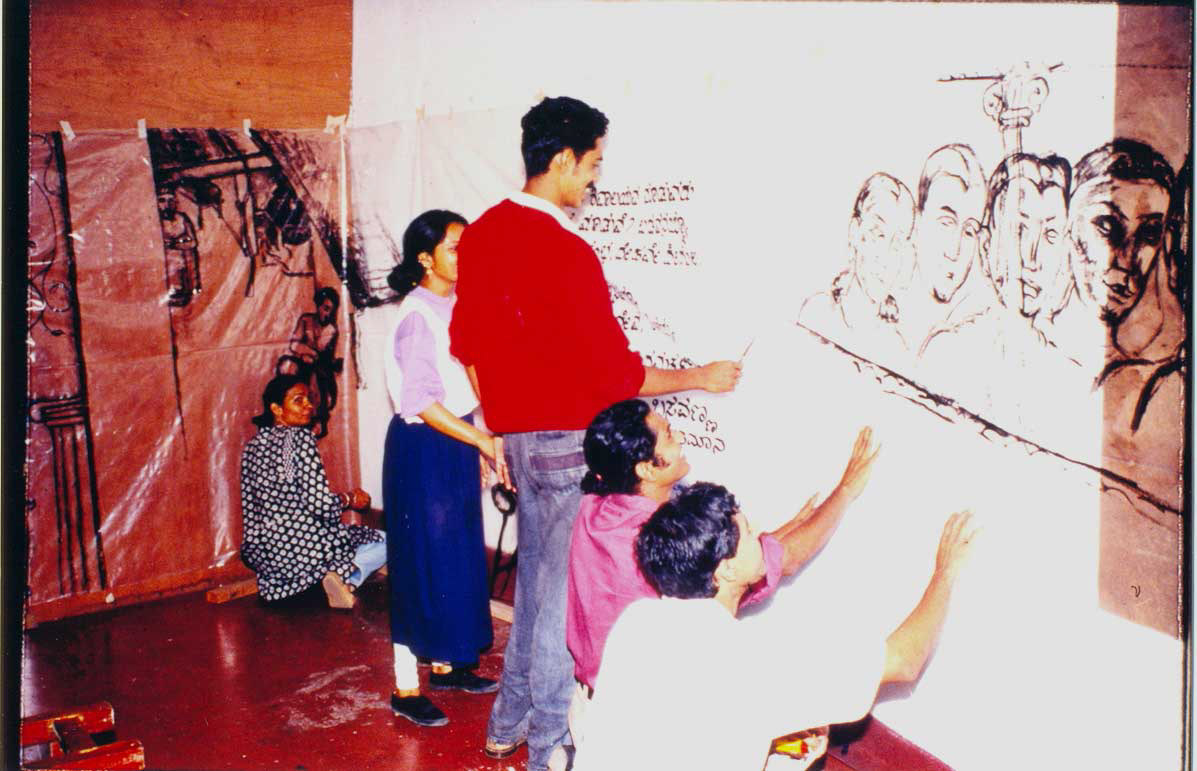

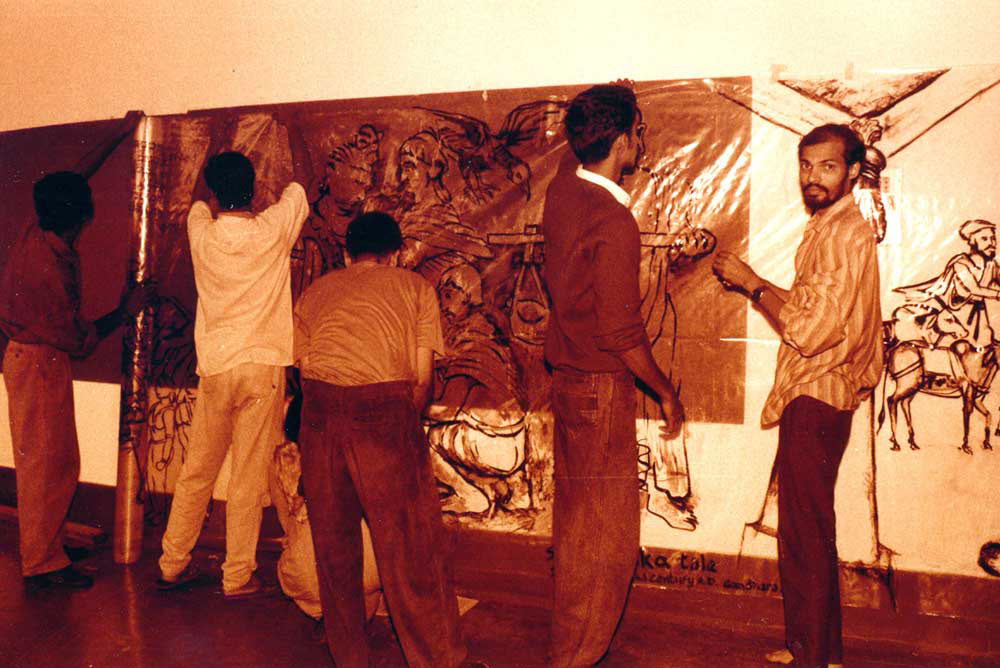

When I returned from Wayanad I saw a request from Girish Karnad's wife Saras to help mount a show arranged by Sahmat, Delhi. The show aimed at affirming and celebrating the pluralistic vision that we had upheld for ages. I agreed to help mount the show. Also I thought creating a work as a personal response to the questions arising from communal tensions that prevailed. To my thinking, the most that artists connected with the public in post-independent India was during this time. Many visual responses by artists were heartfelt calls for communal harmony. Other kinds of responses included satire. These responses wrestled with communal minds, asking the nation not to be blinded by sectarian politics. Other works, particularly those presented by Sahmat, had well researched materials on cultural and historical evidences of how different communities have influenced and enriched one-another in food, clothing, architecture, art, culture and in sensibilities. All these were important in disseminating a collective will to preserve the beauty and rich harmonious diversity of our polity.

I felt there was an underlying honest and serious spiritual apprehension among many people, particularly among the urban populace, in the country. When we look at communal issues we need to look into this question too. Life, in all aspects -- cultural, social, economic, political and also spiritual -- was in flux. Without our own knowledge we were sucked through a process of alienation, commodification and weaponization, resulting in a spiritual vacuum. I thought the best means to look into our communal minds and help us towards a transcending vision is to understand our own spiritual nature and questions. People from all walks of life in all times in history have asked themselves questions to understand the spiritual nature of their own being. Questions about life, death, god, meaning even if one is an atheist. The best minds that can serve as guides are Kabir, Akkamahadevi, Basavanna, and various others.

I conceived an installation, the first installation, created out of two intertwining spirals to express the questions and understandings the seekers have offered to us through history. Sitting at Ashirvad on St. Marks Road I shared my thoughts on this installation project with artist Sheela Gowda. Sheela said, 'Yes, let us work on it'. She contacted Rasna Bhushan and we invited some more artist friends, including Raghavendra Rao and Sureka to help execute the work. Both Sheela and Rasna helped gather the relevant texts and images to be used in the work. We dove into materials from Kabir, Akkamahadevi, Allama Prabhu, Basavanna, Jesus, Buddha, Sri Narayana Guru and others who helped nations transcend the dogma of their times.

Challenges

Some from the secular movements took objection to the fact we were using material connected with religion. The activists of the time who were arguing for secularism tried to do away with any form of expression that had any link with religion. But many people spent a lot of time inside the spiral. The moment one enters the work, she of he also becomes part of the work. Because of the semi transparent quality, as the viewer moves into inner layers of the maze become faded creating an interesting image that weaves and blends itself with images and texts. Many students who were in the installation spent time guiding the viewers. Since it was a maze if one did not proceed correctly, he or she would end up where they began. It was a common to see people end up at the entrance of the installation again and again. I used to hear students telling the viewers from inner circle of the maze…

"Keep moving forward without turning, so that you can reach the other end."

C.F. John

In the Name of the Secular – Contemporary Cultural Activism in India, Oxford India Paperbacks, Rustom Bharucha

"The installation was in the form of a spiral maze. Two intertwined spirals over 100 feet each in length and 6 feet in height with 4 feet space between each layer were installed. (please refer to drawing). The material used was plastic. The transparent surface of the plastic made it possible to weave together visuals and the viewers from different layers. Hence, contemporaneously the images, installed space, and viewers become integral components of the work.

Visuals and texts, both in English and in Kannada, were taken from various counter cultural/religious movements from history that countered the dogmatic religious stands of the time. These visuals were painted or drawn on the plastic surface of the spiral. Two parallel mirrors were placed facing each other in the center of the maze where the viewer could see him/herself. The spirals placed emphasis on self-realization rooted in fundamental human values in relation with the Earth…

Visuals and texts, both in English and in Kannada, were taken from various counter cultural/religious movements from history that countered the dogmatic religious stands of the time. These visuals were painted or drawn on the plastic surface of the spiral. Two parallel mirrors were placed facing each other in the center of the maze where the viewer could see him/herself. The spirals placed emphasis on self-realization rooted in fundamental human values in relation with the Earth…

This was a cultural spiral in plastic, which incorporated non-canonical texts from Buddhist, Bhakti, Sufi and Christian philosophies painted in black on its surface. Serving as an environment rather than as an art object, the spiral offered viewers the possibility of experiencing an inner journey, as they walked through the structure and encountered themselves at the vortex of the installation with an image of themselves, reflected in two long mirrors. Then, along another path, they would journey through the spiral to the world outside.

Tuning into the political dynamics of this secular space, Janaki Nair has rightly highlighted the ‘self’ as one of the most elusive, yet crucial components in shaping secular consciousness. The process of self-confrontation combats both the ‘regime of censorship’ instituted by the agent sof the Hindu Right, as well as the obligatory secular dependency on ‘cultural pluralism’, which can so often be trivialised within ‘the grab-bag of syncretist traditions’ (Nair 1993; 39). Countering these forces, the construction of the ‘secular self’ can draw more meaningfully on the principles of specific cultural resources. In this regard, the choice of the mirrors in the spiral by the chief architect C.F John, was directly inspired by the centrality of the mirror as an image in the ritual celebration of Vishu (new Year) in Kerala, when ‘family members are woken up to a bountiful sight of fruits, flowers, gold, and coconut – but, above all, of a mirror in which they see themselves’. The mirror is also one of the most complex emblems of transition between ‘everyday life’ and ‘performance’ as the auspicious moment when the actor is transformed into another being, another self.

Here again, one notes how an image drawn from a religio-cultural tradition can be effectively secularised with the necessary ideological intervention and the use of particular materials. Plastics, for instance, as Nair points out, was a deliberate choice for the spiral, partly because of its transparency, which enabled the viewers to see the texts along with the bodies of other spectators. This heightened an awareness of collective participation in a visual act – a participation that was both countered and counterpoint by the moment of solitude in the vortex of the spiral. Another reason for the choice of plastic was its ‘synthetic’ challenges to the ‘organicity of vision’ offered by the upholders of a single, unified, eternal Hindu vision of India. It was also through the very contemporaneity of its material that the use of plastic could debunk the ethnicity of indigenous materials that are so often valorised in the national commodification of Indian culture in festivals at home and abroad.

Here again, one notes how an image drawn from a religio-cultural tradition can be effectively secularised with the necessary ideological intervention and the use of particular materials. Plastics, for instance, as Nair points out, was a deliberate choice for the spiral, partly because of its transparency, which enabled the viewers to see the texts along with the bodies of other spectators. This heightened an awareness of collective participation in a visual act – a participation that was both countered and counterpoint by the moment of solitude in the vortex of the spiral. Another reason for the choice of plastic was its ‘synthetic’ challenges to the ‘organicity of vision’ offered by the upholders of a single, unified, eternal Hindu vision of India. It was also through the very contemporaneity of its material that the use of plastic could debunk the ethnicity of indigenous materials that are so often valorised in the national commodification of Indian culture in festivals at home and abroad.

I have dwelt at some length on this installation because it seems to me that the spiral offers one of the most potent visual signs of our emergent secular culture. In its form, one can discern movements that are reflexive and curvilinear, resistant to the certainties of straight lines, and yet directed in its search of the unknown. Tellingly, the journey inwards can also be a shared experience”.